Our littlest learners thrive when supported by high-quality child care. Still, there isn’t enough high-quality child care to go around. And what does exist is difficult to access. National and state-level studies show that barriers to child care limit the economic potential of parents and businesses alike.

In other words, parents are staying out of and withdrawing from the workforce if they can’t secure quality child care. And it’s costing everyone.

With a mandate to support full employment, the Fed seeks to better understand the economic challenges limiting the availability and affordability of high-quality child care. Our research helps inform solutions. And identifying evidence-based solutions can yield long-term benefits for the US economy.

To this end, researchers from eight Federal Reserve Banks meet regularly in a working group focused on early childhood education. Our group recently published two reports on supply constraints and demand challenges that hinder equitable access to quality child care.

Child care supply and demand

In the first report, we examine public investments in the child care market, primarily comprised of privately-run businesses. The report also presents examples of three innovative interventions aimed at supporting child care providers and professionals.

The second report focuses on the demand for affordable care that meets the needs of parents and children. It emphasizes economic data highlighting the importance of child care for the broader workforce.

Damage to productivity

Parents regularly report child care interruptions and breakdowns threatening their productivity at work. These sorts of reliability issues result in an estimated $122 billion of annual lost economic output according to a study by ReadyNation. That study’s methodology and findings are similar to studies of state-level child care economies by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation.

Wondering how the lack of affordable and reliable child care impedes workforce participation in your state? The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis has state-level snapshots based on recent research. To give you an idea of the type of information you’ll find, here’s a snapshot from the series, Child Care and the U.S. Economy, focused on the national picture. Takeaways include:

CHILD CARE AND THE US ECONOMY

Child care is a key support for the US workforce.

53% of those working in the US are parents.

37% of those parents have young children.

Access to child care is especially critical for Black mothers.

62% of Black mothers with young children are single parents, compared with 38% of Latina mothers and 21% of white mothers with young children.

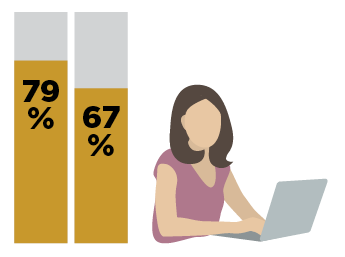

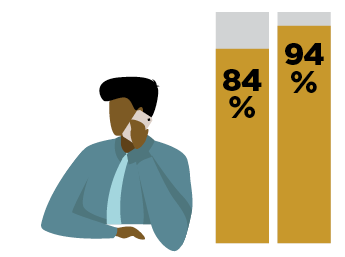

Young parenthood boosts men’s labor force participation

but depresses women’s labor force participation.

79% and 84% of childless US women and men, respectively, participate in the labor force.

Corresponding figures are 67% for mothers with young children and 94% for fathers with young children.

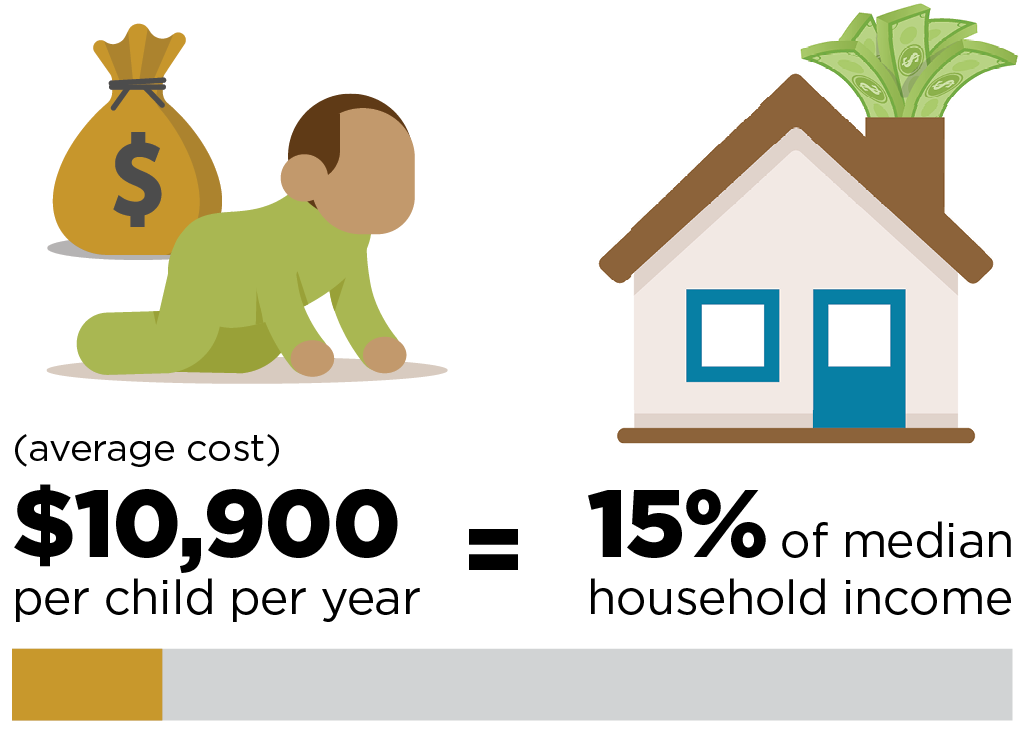

High child care costs challenge families with young children.

The child care industry is struggling.

The child care workforce has decreased by 11% in the US since the start of the pandemic.

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (via IPUMS CPS), U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (via IPUMS USA), Child Care Technical Assistance Network, Bureau of Labor Statistics Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages and the authors’ calculations.

Download this fact sheet (jpg, 481kb)

Affordability struggle

How is the child care economy financed? Most of the money comes from parents who pay out-of-pocket. Another source is government dollars. One estimate suggests that parents spend about $54 billion on child care annually. This amount far surpasses the $29 billion invested in early childhood education by all local, state, and federal governments in a typical year.

Many parents struggle to afford this essential service. In one analysis, the average tuition for child care would eat up about 10 percent of the median income for a two-parent, two-income household in many states. The burden is heavier on single parents: the same care would cost a median-income single-parent household about 32 percent of its earnings.

Government support lowers child care costs for some low-income families.

The Child Care Development Block Grant is the largest public funding source for child care assistance. In a typical year, about a quarter of children are eligible under federal guidelines for the CCDBG. Only 15 percent of these eligible children receive assistance.

As a result, the high cost of child care remains a major impediment for parents seeking it. On top of the high cost, the limited availability of child care presents a challenge. This is especially true for parents with nontraditional work hours, such as evenings and weekends.

Unreliable supply

Many providers operate on thin margins. They struggle to stay afloat even as their customers struggle to afford their services. Reliance on parents for revenue combined with limited public investments contributes to the fragility and inconsistency of the supply of child care.

Child care itself is physically and emotionally demanding work that is overwhelmingly done by women – and disproportionately by women of color. But wages for early educators in a classroom setting – one of the key components of the child care workforce – have persistently been among the lowest for any job tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

And workers are responding. Fewer workers provide child care today than in February 2020, prior to the onset of the pandemic. Child care provider surveys suggest that the country’s overall child care capacity is likely being squeezed by these workforce challenges.

These supply shortages can put parents at greater risk of facing child care disruptions, which impacts their ability to work and earn.

Finding ways to connect children with care

The community-designed interventions we highlight in both reports aim to bring more stability to parents and child care providers alike. These innovations, combined with the data, research, and strategies we present, shed light on the current state of the child care market and offer options for removing obstacles to more equitable access to child care. The people behind interventions like these are striving to build a world where more working parents and would-be working parents can find what they really want: affordable, reliable options for keeping their children safe and meaningfully engaged while they work.

Connecting Communities:

Two sides of one child care dilemma

Families want quality early childhood education (ECE) but it’s often competitive to access and costly, especially for care during nontraditional hours. Providers face financial constraints of their own. In this webinar, experts discuss findings from recent research.